The three mechanics are an important part of understanding Bitcoin on a technical level.

Learning Bitcoin With Charts: How Are Hash Rate, Difficulty And Fees Related?

Date: May 15, 2021

Bitcoin’s difficulty adjustment mechanism is one of its most important aspects, but learning how it works can be a daunting task. This article leverages on-chain data to visualize how this mechanism works and how it relates to hash rate, block intervals, transaction fees, and the mempool. After reading this article, you will have a better understanding of why at certain times using Bitcoin may appear to be relatively slow and expensive, but also how Bitcoin fixes this and why this process is so essential to ensure Bitcoin’s monetary properties.

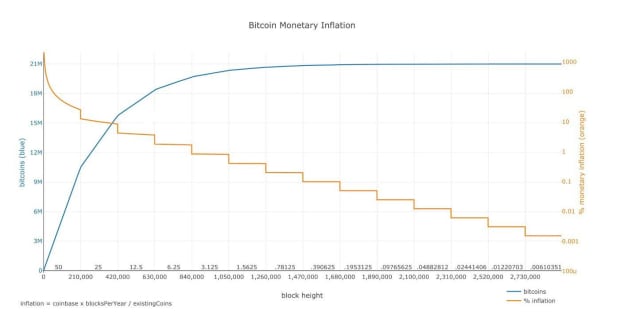

Bitcoin’s Supply Issuance Schedule

If you have heard of Bitcoin, you have probably heard that its supply is hard capped at 21 million units (BTC), making it a perfectly scarce asset and thus the ultimate “hard money.”

When Bitcoin was created, miners received 50 BTC for each new block as a reward for their work. The software has a built-in rule that after every 210,000 blocks that are mined (approximately every 4 years, if the block interval is 10 minutes), this “block subsidy” is cut in half during an event called “the halving.” During this first “reward era”’ which ended November 28, 2012, 10.5 million BTC were mined — half of its maximum supply. During the second reward era, half of that amount (10.5 million / 2 = 5.25 million) was issued, followed by half of that (5.25 million / 2 = 2.625 million) during the third reward era — and so forth. After 32 halvings, the block subsidy equals the smallest unit in Bitcoin (0.00000001 BTC = 1 sat) and cannot be split after, which means the block subsidy falls away completely after that (believed to be in the year 2140, if block intervals were 10 minutes during its entire existence). The first 14 reward eras of Bitcoin’s issuance schedule are visualized in figure one.

The careful reader will have noticed that in the previous paragraph, we mentioned twice that the actual calendar dates on which these halving events occur depend on the block intervals and that we assumed 10 minutes here. Why is it important that this supply issuance schedule is predictable in regular calendar-times in the first place?

The Importance Of Relatively Stable Block Intervals

Let’s consider what it would look like if Bitcoin didn’t have a built-in difficulty adjustment mechanism, but simply had a fixed mining difficulty.

If that fixed difficulty had been set relatively high, early mining would have been very expensive and blocks would have come in at a very slow pace early on. Clearly, that wouldn’t have been ideal to bootstrap a new network and could have meant that it never succeeded in the first place.

On the other extreme, if the difficulty would have been set relatively low to incentivize early network participants to join, block intervals would have gotten smaller as more miners joined the network, and blocks would have come in at an increasingly quicker pace. It would have quickly run through its entire supply issuance schedule. Had this happened, the Bitcoin network likely wouldn’t have had enough time to develop the block space market needed to sufficiently incentivize miners to keep mining blocks in order to process transactions and secure the network after the block subsidy had run out.

To summarize, relatively stable block intervals are needed to spread out Bitcoin’s supply issuance over time, which in turn is needed to incentivize miners to keep joining the network over a relatively long bootstrapping period, as well as to gradually develop a block space market that will be able to keep the lights on after the block subsidy reward runs out.

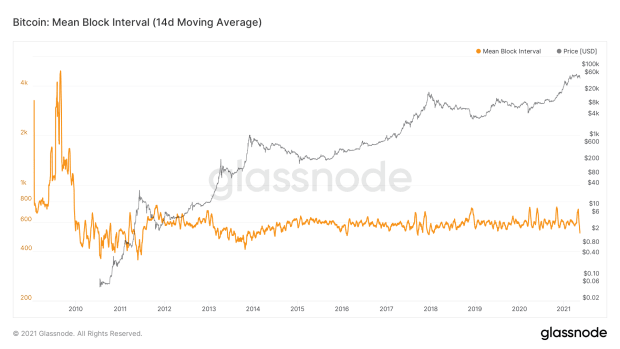

To guarantee that block intervals will remain relatively stable over a multi decade period, Bitcoin has a difficulty adjustment mechanism. As can be seen in figure 2, even with this built-in difficulty mechanism, its block intervals were not very stable, averaging much longer than 10 minutes per block during its first year of existence. The block intervals became more stable after Bitcoin set its first market price in July, 2010, and have been relatively stable at just under 10 minutes for over five years now (no structural up or down trends in the orange line in figure 2) – works like a charm.

Bitcoin’s Difficulty Adjustment Mechanism

To mine bitcoin, miners use highly specialized computers to basically guess a certain number (slightly simplified explanation). When a miner finds the number that the network is currently looking for, that miner earns the right to create a new block on the Bitcoin blockchain, take its block subsidy, choose which transactions to include in that block, and collect the fees of those transactions. At the time of writing, all miners that are active on the Bitcoin network are estimated to have a total capacity (hash rate) of 170 exahashes per second (EH/s), which is 170,000,000,000,000,000,000 hashes per second.

In Bitcoin’s first year of existence (2009), it was still possible to mine Bitcoin on the Central Processing Unit (CPU; which is basically the central chip in a computer that takes care of lots of things) of an average consumer computer, as the network’s hash rate was just a few million hashes per second. Over time, more computers joined the network and eventually chips that were better at heavy number crunching via their Graphics Processing Unit (GPU), the chip in a computer that is applied for graphical tasks and linear algebra) or even hardware custom made for Bitcoin mining (an ASIC, or Application Specific Integrated Circuit) was used.

As you can imagine, as the network’s hash rate increased by a multi-trillion-fold from that first year until now, it was necessary to make it a lot harder to guess that certain number to ensure relatively stable block intervals of approximately 10 minutes each

In Bitcoin, “difficulty” is the measure for how hard it is to find that number that the network is looking for. Every 2,016 blocks (14 days if block intervals are 10 minutes), the Bitcoin software basically calculates the block intervals during that period and adjusts the difficulty so that at current capacity, the average block interval will be roughly 10 minutes again.

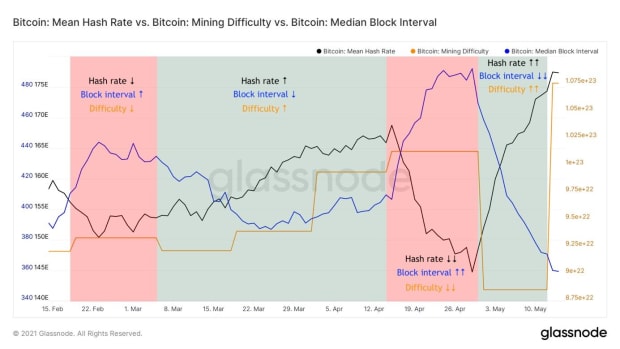

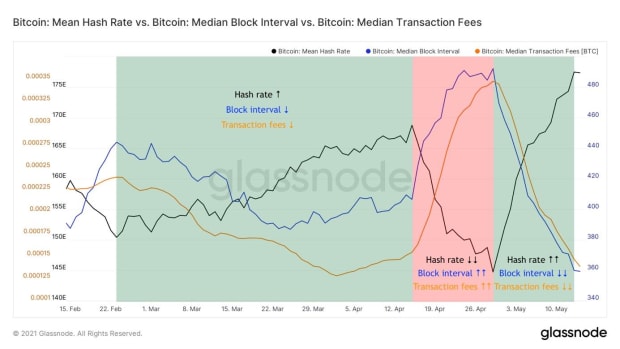

The interplay between Bitcoin’s difficulty (the 14-day moving average of the) hash rate and block intervals over the last three months is visualized in figure 3. During the first visualized difficulty adjustment period (the red column on the left), the hash rate was declining (downtrend in black line). As network capacity decreased, block intervals increased (uptrend in blue line), making it necessary to decrease the difficulty (small drop in orange line after this period).

In three difficulty adjustment periods after (first green column in figure 3), the hashrate was increasing again, blocks came in faster than planned and difficulty adjusted upwards three times. Mid-April, 2021 (right red column), there was a large power outage in China that caused a massive drop in Bitcoin’s hash rate, slowing down blocks a lot and making a huge downwards difficulty adjustment necessary after the period. After this happened (right green column), the power outage itself was solved and the downwards difficulty adjustment made it much easier for miners to create blocks again. As a result, some miners with less efficient hardware and/or more expensive energy could earn a profit mining again, actually overcompensating the previous loss of hash rate, actually sending it to new all-time highs.

This latest hash rate drop and recovery is a good example of why miners leaving the network does not have a cascading effect of more miners leaving the network (sometimes called the “mining death spiral” by critics), but the software simply increases the remaining miners’ profit margins, incentivizing other miners to (re)join the network.

Transaction Fees

A side effect of this mechanism that we all feel is its impact on transaction fees. During times when the hash rate increases and blocks are coming in faster than planned (green columns in figure 4), transactions can relatively easily be included in blocks. Since this means that there are less transactions queued up in line (in Bitcoin called the “mempool”) to be included in upcoming blocks, transaction fees can be relatively low.

The opposite is true during periods where hash rate drops and block intervals increase (red column in figure 4). When blocks are coming in slowly, the queue of transactions waiting to get included gets crowded, and people need to bid up their transaction fees to basically jump the line. As such, transaction fees spike especially when the network capacity decreases (hash rate drops) and is waiting to be bailed out by the next difficulty adjustment.

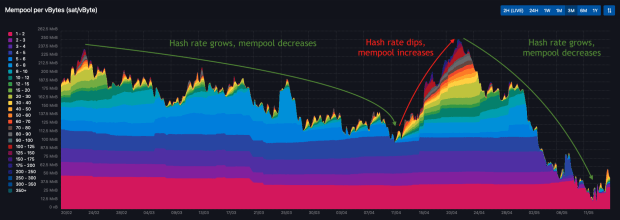

In this section, we discussed the fees of transactions that were included in blocks. For those looking to transact on the Bitcoin network, it is even more relevant to get a feel for how much all of the transactions that are still waiting in line to be included in future blocks are bidding for their needed block space.

Mempool

As briefly mentioned above, the Bitcoin mempool can be interpreted as the total of all transactions which were broadcast on the network but are still waiting in line to be included in a future block. Technically, each of the thousands of Bitcoin nodes on the network has its own mempool, but since they are mostly well interconnected, visualizing them as a single waiting line is alright for general explanatory purposes.

Mempool.space is an industry-standard website that gives anyone not running their own node or simply looking to get a quick look at the mempool all the relevant data. Examples are the total size of the waiting line (mempool size), how many transactions are joining the queue (incoming transactions), if blocks are coming in faster or slower than expected (estimated difficulty adjustment) and estimations of how high the transaction fee of a new transaction needs to be to be included at low, medium, or high priority.

Figure 5 visualizes the mempool of the last three months. As you would expect, the patterns described in figure 4 can also be seen here. Between late February and early April 2021, when the amount of hash rate on the Bitcoin network increased and more blocks than planned were created, the mempool size (the size of the waiting line) decreased and transaction fees decreased correspondingly. After the mid-April hash rate drop, the mempool quickly increased and transaction fees skyrocketed, but both declined quite quickly after the April 30th difficulty adjustment, and subsequent hash rate growth to all-time highs.

The Future Block Space Market

As briefly mentioned at an earlier point in this article, Bitcoin’s block subsidy is designed to decay over time, and the development of a healthy block space market where transaction fees become the primary source of revenue for miners is essential to incentivize miners to keep processing transactions and securing the network in the long-run.

This is possibly the most important test that awaits Bitcoin in the future, and is the subject of my previous Bitcoin Magazine article titled “An Ode And Forthcoming Obituary To Bitcoin’s Four-year Cycle,” which is a recommended follow-up read. Finally, if you have any questions on the topics discussed in this article, feel free to send me a message on Twitter.

Disclaimer: This article was written for educational and entertainment purposes only and should not be taken as investment advice.

This is a guest post by Dilution-proof. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC, Inc. or Bitcoin Magazine.