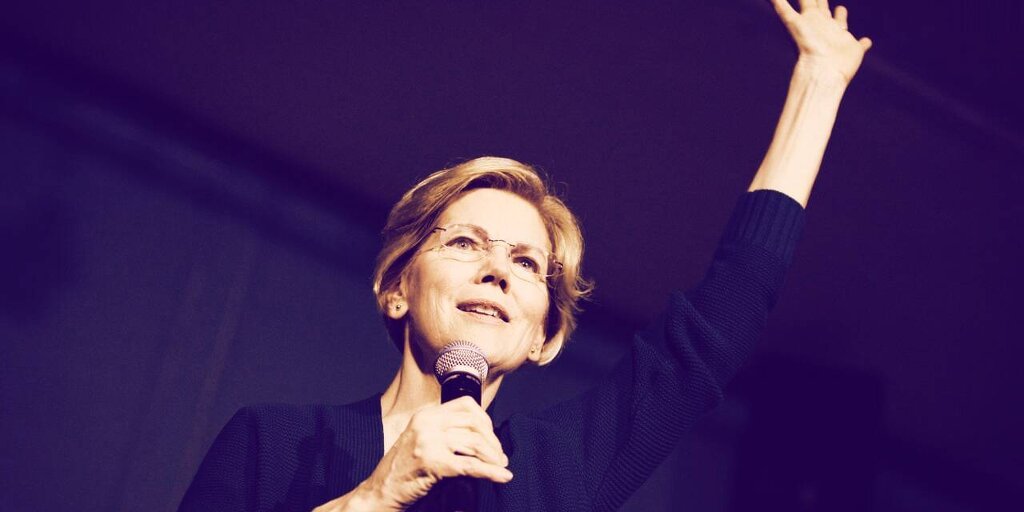

During a hearing on the development of a potential central bank digital currency, Senator Elizabeth Warren criticized cryptocurrencies for their role in facilitating scams, ransomware attacks, and pollution.

In her opening statement, Warren called crypto a “fourth-rate alternative to real currency,” thanks to its being a “a lousy way to buy and sell things,” “a lousy investment,” and “a haven for illegal activity.”

“Unlike the dollar,” said Warren, “their value fluctuates wildly depending on the whims of speculative day traders. In just the last two months, the value of Dogecoin increased by more than tenfold, and then declined by 60%,” she said. “That may work for speculators, and fly-by-night investors, but not for regular people looking for a regular source of value to get paid in and to use for day to day spending.”

But Warren made clear that her criticisms weren’t limited to just Bitcoin or Dogecoin. Most cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile, she reasoned, which makes them difficult to use as a medium of exchange. She also cited crypto’s lack of consumer protection laws, which leave little legal recourse for victims of scams. As for how crypto facilitates some forms of illegal activity, Warren mentioned recent ransomware attacks on Colonial Pipeline and JBS, a meat supply company, both of which involved crypto payments.

“Every hack that is successfully paid off with a cryptocurrency becomes an advertisement for more hackers to try more cyberattacks,” argued Warren.

When Bloomberg initially reported that Colonial Pipeline had paid a ransom to a Russian collective called DarkSide, it claimed the company executed the payment in an “untraceable cryptocurrency.”

“Untraceable” doesn’t typically refer to a cryptocurrency like Bitcoin, which records transactions on a public ledger. Savvier criminals, as we reported at the time, tend to stick with privacy coins, such as Zcash and Monero.

It turned out that DarkSide did ask for Bitcoin—and just a few weeks later, the U.S. Department of Justice managed to recover part of the ransom. So some attacks, at least, aren’t great advertisements for the benefits of crypto as a tool for criminal activity.

Warren’s remarks were part of a broader point about the differences between the promise of crypto as articulated by its loudest proponents, and the reality of how these technologies are currently being used.

“Crypto’s promises haven’t come to pass,” she said.

Warren also asked Columbia Law professor Lev Menand whether stablecoins—a type of cryptocurrency that’s pegged to the value of a fiat currency, and so theoretically maintains a “stable” price—could be a reliable alternative to a digital currency controlled by a central bank.

“Certainly not,” he said. “They’re dangerous to both their users, and as they grow, to the broader financial system.”

Part of this reasoning has to do with the idea that if people lose confidence in stablecoins, bagholders might just dump them en masse. “The people who are slow to get out could be left with significant losses,” explained Menand.

This isn’t a hypothetical—the value of Tether, the most valuable dollar-pegged stablecoin, fell to $0.95 during last month’s market crash.

Warren also mentioned what’s become the most common critique of cryptocurrency: that it incentivizes world-historic levels of energy consumption, much of which ends up coming from power grids reliant on fossil fuels.

Even still, Warren was open to the possibility of a central bank digital currency—something backed by the U.S. government, and subject to regulation.

“Legitimate digital public money could help drive out bogus digital private money,” she said. “It could help improve financial inclusion, efficiency, and the safety of our financial system if that digital public money is well-designed and efficiently executed, which are two very big ‘ifs.’”