When Dreamfield, a new platform to connect college athletes with companies for endorsement opportunities, centered its entire splashy rollout on July 1 around NFTs featuring its two quarterback co-founders, the timing might have looked late.

The media had already declared NFTs dead in the first week of June, when the New York Post, Gizmodo, Hypebeast, and Quartz, among many other sites, all gleefully reported that sales of blockchain-based collectibles had peaked in May. NFL players like Rob Gronkowski, Vernon Davis, and the Manning brothers already made their NFT money back in March and April.

But now NFTs, tokens that function as proofs of ownership in digital items, are suddenly roaring back. NFT marketplace OpenSea says it processed $95 million worth of NFT sales last weekend alone; OpenSea had $21 million in sales volume in all of 2020. The average price point for a CryptoPunk (an ancient, high-value NFT series of unique pixellated faces) skyrocketed 53% in the past week to $135,000. Social media influencer Gary Vaynerchuk bought a CryptoPunk for $3.7 million last week, while Stoner Cats, an animated web series from Mila Kunis and Ashton Kutcher, sold $8.3 million worth of NFTs.

And now Dreamfield’s plan to incorporate NFTs into its college athlete marketing approach looks pretty savvy.

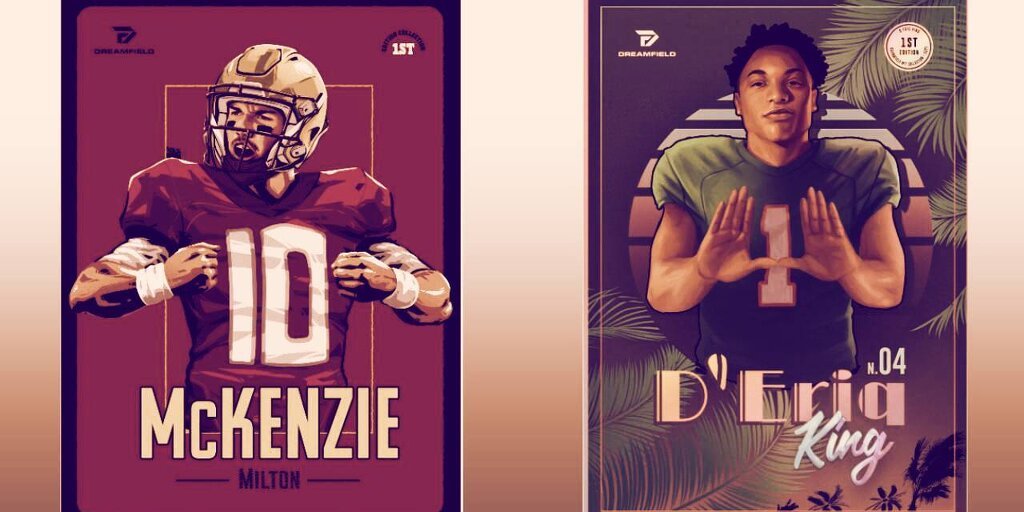

Dreamfield’s athlete co-founders are University of Miami quarterback D’Eriq King and Florida State University quarterback McKenzie Milton, and Dreamfield announced at launch that both would get NFTs commemorating their careers so far, specially designed by artist Black Madre. The NFTs are now up for sale on OpenSea; they start with original animations, then end with video footage of the quarterbacks addressing their fans.

It all came together when the NCAA rules prohibiting college athletes from making business deals dramatically changed, effective July 1: student athletes can now profit off their name, image, and likeness (NIL). King and Milton immediately went public with Dreamfield, which will function like a Cameo for connecting athletes with small businesses looking to pay them for appearances or promotions. Not every athlete that signs with Dreamfield will have an NFT, but King’s and Milton’s are a standard Dreamfield hopes to repeat.

“We’re looking at them for higher-profile athletes, and we’re calling it their pre-rookie cards,” Dreamfield CEO Luis Pardillo tells Decrypt. He also sees opportunities for athletes in crypto marketing beyond just NFTs: “We think we can be the bridge to connect athletes to companies in the crypto space in a safe and smart way.” (Look no further than Trevor Lawrence, the former LSU quarterback, signing with FTX-owned Blockfolio just in time for the NFL Draft, where he was the No. 1 pick.)

Dreamfield says more than 300 athletes, and over 200 small businesses, have already signed up. But it’s hardly the only company rushing into the college athlete marketing race in the wake of the new NIL rules. Barstool Sports quickly set up an athlete marketing division, and NBA player Spencer Dinwiddie tells Decrypt he aims to recruit some college athletes to Calaxy, his social token platform for influencers.

King and Milton were far from crypto natives before Dreamfield, but say they’re hearing more about the topic than ever. “I would say NFTs are the future,” King says. “I know it’s here now, but still it’s brand new. And the crypto aspect of it is pretty cool. I think it’s definitely a conversation in the locker room.”

Milton’s NFT combines imagery from his time at University of Central Florida (Pardillo is an alum and met Milton’s mother at an alumni event) and FSU, where he’s about to play a postgrad season and is expected to be the starter. He points to Yummy Crypto’s NIL deal with the University of Miami basketball team as something that gets him excited about the industry.

“I could definitely see a lot of that happening in the near future with several universities, especially with them being a charitable token,” he says. (Yummy donates 3% of crypto transactions to charity.) “Even my buddy today was like, ‘Bro, we should make a Seminole token after the first game.’ I said, ‘How are we going to do that?'”