Bitcoin is poised to fix the fiat-created problems which inhibit potential progress.

In the year my grandfather was born, the supersonic jet engine, synthetic rubber and the modern microscope were all invented. The year my father was born, the laser and the halogen lamp were both invented, and the first GPS satellite was launched into space. The year I was born, the modern web was invented by bringing Tim Berners Lee’s proposal: “WorldWideWeb: Proposal for a Hypertext Project” to life with the first website.

Last weekend, I was out for a morning walk with my dog and got a push notification onto my phone; Eric Weinstein was talking on Clubhouse. The room was titled, “Why Are Scientists, The Media, And Our Politicians Lying To Us?” For those that don’t know Weinstein, he is a heterodox thinker, managing director of Thiel Capital and the person who coined the term “The Intellectual Dark Web.” In the past year, he has had some brushes with the Bitcoin community at large, though that is not the focus of this article.

I’ve listened to Weinstein for years as he is able to lay out mental models that help me see the world differently, or as he calls them “Portals,” a phenomena he named his podcast after: “The Portal.” Weinstein attributes the cross-institutional decay of academia, media and politicians to an idea that caught my attention; “Embedded Growth Obligation.” I had heard this term before, on his inaugural podcast episode from 2019 with Peter Thiel labeled; “An Era of Stagnation and Universal Institutional Failure.”

I went back and listened to that episode — the three-hour discussion that followed is the inspiration for this article. I hope to lay out some foundational ideas that were discussed between the two of them, and how Bitcoin fixes this to Eric’s chagrin.

Let’s set some terms. Institutions are a key part of the discussion, so a precise definition will build a strong foundation. Institutions are a group of people that self organize with a shared common goal. The Catholic Church, New York Times, and your local sports teams are all examples of institutions. Institutions serve a vital role in a healthy culture as they align individuals to operate as groups on agreed terms. If you’re a member of the local Parent-Teacher Association board, all issues that are not about educating the children are not part of the conversation. Institutions act as sensemaking organs, as individuals with a shared goal can have dialogues pushing a cause greater than themselves forward. That is, when the institution is healthy.

The embedded growth obligation (EGO) is how fast an institution has to grow for it to maintain its honest positions. Conveniently, it can be thought of as the ego a particular institution has. Take a very simple example in which this is easily identifiable: universities. A professor teaches a collection of grad students, many of whom wish to become professors themselves. When these students graduate, many may wish to go on to become a professor to teach their own cohort of grad students. Anyone familiar with a Ponzi scheme can see that this is very quickly unsustainable after a few cycles as you need many new grad students for each new professor.

Weinstein and Thiel posit that when growth stops, our institutions become parasitic and sociopathic. Institutions begin disregarding their stated purpose and looking inward, trying to grow at all costs. Furthermore, they insulate themselves with a priestly class of experts who claim to have sole authority over what is true and even construct the means by which we measure our reality. A prime example of this would be inflation.

Our trusted class of economists that tell you inflation is not the money supply increasing, but an elaborate series of calculations and weightings to assert that inflation is only 5.4% year over year.1 If you look at the M2 Money supply, a metric that is not gameable, 30% of all money that ever existed was created since January 2020.2 Furthermore, 75% of all money was created since the 2008 financial crisis,2 but if you use government-provided calculators, $1 from January 2008 is “inflation adjusted” to be $1.24 in January 2021.3 If institutions are part of our collective sensemaking organs, and they play a role in obfuscation rather than truth seeking, what does that do to societies?

Institutional betrayal is a concept introduced by Jennifer Freyd; to summarize, when an institution with a caretaking role is deceitful, defying its mandate, individual trauma extends beyond the individual agents that have done wrong, but to the larger and structure of society.4

College students are taking ever increasing amounts of debt, subsidized by our government. The economic data is clear: We are paying more for a lower quality service.5 Student loans no longer serve the college student but the institution of “education.” The institution is further entrenched in power by coordinating with governments to enact policies that make discharging of (or refinancing) student debt illegal, yet every other form of debt can be refinanced or forgiven through the courts. The education system traps the individual, in service of upholding the institution of “education.” The institution has transcended from being a means to the chief end goal.

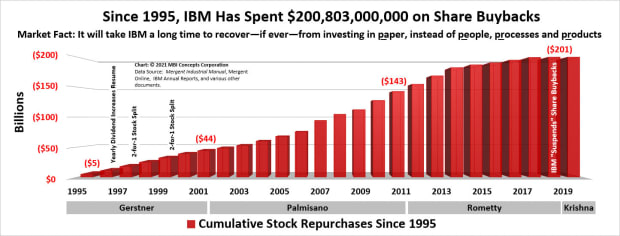

No institution is exempt from the treadmill that is EGOs. Take, for example, a large technology company like IBM. Since 1995, IBM has spent $201 billion on stock buybacks. IBM today has a market cap of $127 billion dollars, clearly showing malinvestment in the 12-figure range.

A prisoner’s dilemma forms within an institution like IBM. Large, publicly traded companies have executive boards whose primary compensation is stock offerings. If increasing the stock value is your path to compensation you’re presented with two paths: Do employees shepherd their company to innovate by making capital allocations to get outsized capital returns? Or do they take existing cash flows and buy their own stock, increasing the share price without altering the underlying business unit economics? It is clear to see what decades of IBM management chose. What is just as compelling is how this is enabled.

Imagine suggesting to your boss — seven levels removed from the CEO — that this is a horrible idea, and that capital be invested in new ventures and not buybacks. This would be actively attacking the embedded growth obligation of executive paychecks. For these leaders, they participate in this shared lie — and every person who wishes to climb the hierarchy of these institutions has to play along.

There is a group alluded to before that is immune to embedded growth obligations: individuals. Individuals who are not reliant on institutions to put food on the table for their family have the freedom to speak the truth. This attribute is what aligns Bitcoiners as allies in the war of addressing this problem. Before we get to how Bitcoin fixes this, we have another “Portal” to explore.

Thiel and Weinstein discuss that, during the late 1960s and early 1970s, there was a moment when technological development diverged. The period that followed, continuing up until today, they call “The Great Stagnation.”

In the world of atoms, the frontier of engineering, the physical world has had little progress over this time period. In the world of bits, we have seen exponential growth in computers, the internet, mobile devices and the tech startups out of Silicon Valley. Moore’s Law, which is the historical trend that the number of transistors on a microchip can double every two years, has been a great source of growth.

To ground this to an example Bitcoiners might understand, look at mining equipment. Bitmain’s S9, a bitcoin miner, was released at the end of 2017, and uses 90 watts to generate 1 TH/s (terahash per second). The S19j released in August 2021 uses 30 watts to generate 1 TH/s. Hardware 3.5 years apart has gained an efficiency of 66%. That is a growth rate that would make even the most ambitious of institutions envious.

Thiel expresses this in a metaphor that drives the point home. Silicon Valley has been aggressively pushing the boundaries of what is possible in building the Star Trek computer to the point where we may even view it as somewhat antiquated, given what people are familiar with today in having a supercomputer in their pocket. You can imagine Captain Picard saying “Hey Siri” — and know we already live in that future world.

On the other hand, none of the accompanying technologies have been developed or seen meaningful progress. There is no warp drive, there is no holodeck, there is no replicator. What progress could be seen in similar fields like 3D printing is moreso technological innovations in the world of bits than it is groundbreaking physical technology.

A lot of the arrested growth (post-1970) is wrestling with the fact that we have made leaps to achieving the Star Trek computer, but nothing else in the Star Trek world. We landed on the moon in July 1969, with less computing power than a TI-84 calculator.6 In the year 2021, there is a big media fanfare because billionaires broke the atmospheric barrier over 50 years later and with five million times more computing power per microchip.7 We haven’t landed on the moon since 1972; where did our ambition go?

Weinstein phrases it another way. If you were to walk into a room and subtract all of the screens, what, beyond style and taste, has truly changed in that room from the 1970s? As a millennial, there is no lived experience of what a 1970s room looked like to validate. Looking through some family albums though, Weinstein is right: Nothing has changed.

The world of bits, though, is not immune to stagnation. The first iPhone and the latest outside of a few cosmetic changes are functionally the same. There are faster runtimes and camera quality thanks to Moore’s Law, but there is no large step function in innovation like the pre-smartphone to post-smartphone era. Anyone in the world of bitcoin mining will tell you that we are starting to hit a wall in additional efficiency to be gained on future-generation miners. What if the parabolic growth in the world of bits that fueled the past 50 years of economic development is about to run out of gas? How do we go forward and what happens to those obligations to the people who were promised something before we were born?

Up to this point, this has been a summation of the two biggest takeaways from that conversation. Embedded growth obligations and the Great Stagnation in the world of atoms. At no point in this three-hour dialogue though is Bitcoin — or even money — mentioned. They are so close! Thiel identifies that the Great Stagnation occurred somewhere between 1968 and 1973, Weinstein targets it as 1971 to 1973.

WTF Happened In 1971?

For those of you who were not aware, Nixon officially closed the gold window in 1971. Up to this point, the entire world operated under the Bretton Woods monetary system. The defining feature of this was that sovereign nations were able to still redeem U.S. dollars for gold. When Nixon closed the gold window, the U.S. dollar fully transitioned to a fiat currency. The crew from wtfhappenedin1971.com have done a great job pointing out that socioeconomic data starts to get a bit weird after 1971. The money is a key part of the puzzle in bridging the source of EGOs and the Great Stagnation.

Let’s walk through how this is unified to the world of Bitcoin.

In 1970, the U.S. had a GDP of $1.073 trillion. In 2020, it had a GDP of $20.93 trillion. That is a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6% over 50 years. That is an impressive growth rate after over half a century! The source of where that growth occurred though is in contention. By no means is all growth fraudulent, we can thank Moore’s Law for a lot of that organic growth, but not all growth is equal. We have to look beyond the top line number to learn more.

Debt markets are where the gaming of growth metrics occurs. When a person, company or government borrows money, consumption and growth happens in the present with resources owed to the future. If too much was being taken from the future to pay for the present (i.e., if there was a demand that outpaced supply of bond issuers), interest rates would rise, illustrating whether or not the debt was truly worth it. Debt means little without the context that interest rates apply, and this is where the second layer of manipulation steps in.

Interest rates are the manifestation of the negotiation between present and future. As interest rates increase, economic miscalculation in the present has a greater punishment, and the greater the reward one has to delay gratifying into the future.

What happens though when an institution has gone parasitic, say the lender of last resort, the Federal Reserve? Since growth has been empowered by borrowing, and the Fed is the backstop to the financial markets, they are the chief growth officer of the country. Understanding mechanically how this is done is important for showing how Bitcoin can fix this parasitic cycle.

Today, when the government needs to spend money it does not have, it will hold a treasury bond auction. These bonds can vary from very short-term lengths of a few months to 30 years. Market participants will buy the outstanding bonds, with the variable “price” being determined as the interest rate. The higher the interest rate, the more bond holders will be compensated for locking their money up in the bond. This, conversely, also means that as interest rates go higher, the government will have to pay more money to issue the bonds.

The Fed is integral to gaming this process to ensure present growth is prioritized over sacrificing for the future. The Fed enters the treasury bond market at a rate of $80 billion per month.8 With this increased “demand” for bonds, the treasury is able to artificially suppress interest rates. Lyn Alden has aptly described this as a restaurant, where the biggest customer is the head chef. It makes no economic sense.

The Federal Reserve and U.S. Treasury Department participate in a ritual, bowing to the altar of embedded growth. Higher interest rates would impact present growth, since it costs more to take from the future to bring to the present. It is no surprise that interest rates had to bend to the will of our EGO.

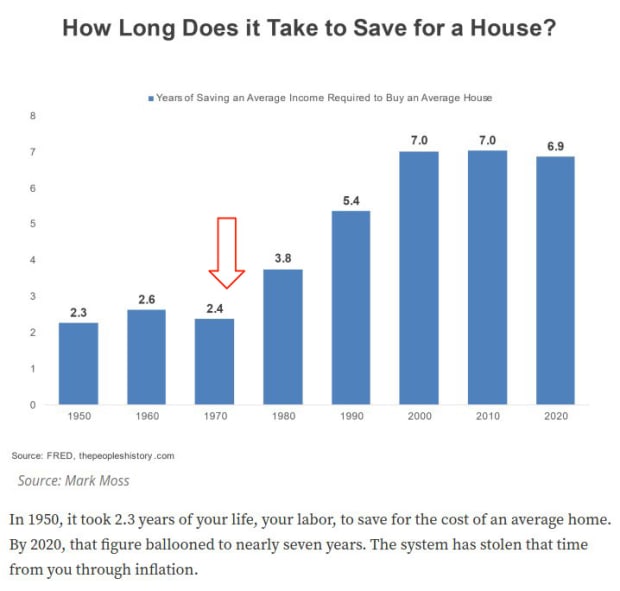

All of this goes beyond treasury bonds, the housing market is at all-time highs, and yet the Federal Reserve continues to put $40 billion per MONTH into buying mortgage-backed securities.8 Not only is your ability to save into the future hurt with lower interest rates, but the things you need in life to have a stable environment to raise a family, like a home, are being monetized out of your reach with ever rising home prices.

The U.S. 30-year bond was first auctioned in 1977.9 Between 1974 and 1977, 25-year bonds were issued. Before 1974, the 10-year bond was the primary debt instrument of the United States going back to 1929. Long-dated debt can have an honest role in a society. For example, an insurance company has long-dated liabilities of paying out policies into the future, so accompanying that with a long-term debt instrument is a responsible way to hedge. What is insidious, is combining long-term debt with interest rate manipulation that has been previously discussed.

The interest rate of a 30-year bond has an implicit agreement. Among those currently at the wheel, how much are they willing to leave to future generations? We often evaluate our leaders based on their generation, from boomers to zoomers and everything in between. It is more complicated than that. Those who are in power have the gun of EGOs pointed to their head, an animal spirit beyond the control of any one person, and will always hit the money printer button. The Federal Reserve, and our elected officials who continue to pass bills with deficits are slaves to the system they helped build.

As the 30-year interest rate drops further, less and less is being left for the future in the service of today’s EGOs. To the point where major countries have gone negative, there is no growth that can be left for the future. Put more bluntly, our ruling class, overwhelmingly from the Silent Generation and baby boomers, are sacrificing the futures of the millennials and Gen Z onto a financial pyre in the service of their one true God — the EGO.

So what do we do as Bitcoiners? We form our own institutions on a founding principle: There will only ever be 21 million bitcoin. There is no EGO in bitcoin’s monetary policy. As Bitcoiners, our aim is to increase our sovereignty, championing individual merit and not bowing to parasitic institutions.

Greg Foss has described bitcoin as a credit default swap on the central banks and money printing. A credit default swap is a financial instrument that prices how much risk is in a given credit market. It’s how Michael Burry made his fortunes betting against the U.S. housing market, as depicted in “The Big Short.” Foss is right, but it goes even further. Bitcoin is a credit default swap on EGOs as a concept.

Bitcoin is able to ride the asset inflation bubble enabled by the Federal Reserve’s policy of easy money. Or as Bitcoiners describe it, NgU (number go up) technology. We all enter bitcoin with the agreement that there will only ever be 21 million and prioritize decentralization and ease of verification as a founding principle. Bitcoin, as a community, holds contempt for experts who tell us we are wrong, and NgU is our receipt. With a fixed-money supply, growth can only be earned not gamed. This founding principle incentivizes delayed gratification and creative capital allocation over consumerism and debt.

How does this impact the world of atoms? The marginal efforts toiling in the world of bits had a much greater financial and political upside because of Moore’s Law. EGOs rewarded the low-hanging fruit of conquering the world of bits. Additionally, the Fed stepping into debt markets and artificially suppressing interest rates to perpetuate growth made riskier long-dated investments in the world of atoms less appealing. With parabolic growth in bits, there is less incentive in trying to conquer the world of atoms. It is hard to quantify the opportunity cost of many great minds that should have been physicists and chemists, and instead ended up being software engineers at a FAANG company trying to increase engagement with advertising by an additional 0.1%. The unfulfilling prospects of working on such problems bubbles up.

Our institutions are failing us as they are in a Malthusian struggle. If natural growth is hitting a wall, all remaining assets are zero-sum conquests. You can only gain more by taking from someone else. That is why so many institutions have become myopic, focused inward on the politics of the day instead of their founding mandates. Bitcoiners though see the world differently, we live in a time of great innovation. Look no further than the world of mining.

In the podcast, Weinstein rightly points out that increasing energy consumption is required for growth and growth puts off violence. Bitcoin, through its proof-of-work mining, enables an opportunity to graft the digital world of bitcoin’s infinite scarcity to the physical world. This fuels an expansion of energy grids to bring more prosperity to the world.

To understand this in more detail, it requires some understanding in how energy works. Two recent interviews that get into the detailed mechanics of energy grids are these interviews with Harry Suddok on “What Bitcoin Did” and Nic Carter’s talk from the B Word conference.

In short, energy grids have several properties that bitcoin can capitalize on. First, once energy is generated, it must be consumed immediately. Second, energy decays greatly when traveling larger distances. Third, there is waste energy associated with some extraction methods that are wasted today.

The promise bitcoin mining has is that it will always buy any surplus energy generated, wherever that is in the world. Both the monetization of stranded energy, and more efficient recycling of energy extraction that would otherwise be vented or flared, can help fund energy projects that were previously unsustainable. This is all done through voluntary market interactions. No need for sweeping legislation or interinstitutional coordination.

As a parting thought, a quote Thiel mentions in that episode of The Portal: “One of the challenges, and we should not understate how big it is in resetting science and technology in the 21st century, is how do we tell a story that motivates sacrifice, incredible hard work and deferred gratification to the future that is not intrinsically violent?”

Bitcoin is an integral piece in answering this question. This goes far beyond personal monetary gain. There is a bright, orange future for Bitcoiners, where we are not caught up in quarterly earnings but on developing intergenerational wealth. It is not enough that we succeed, our great-great-grandchildren that we may never meet must thrive. Bitcoiners will become the capital allocators of tomorrow, with projects that may not have payoffs in our lifetime. Bitcoiners will have a seat at the table to check the parasitic EGO and make sure that Bitcoin as digital and physical truth, will stop the lies and build a better world for our descendants to live in.

This is a guest post by Rob Hamilton. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC, Inc. or Bitcoin Magazine.

Citations:

1 Cox, Jeff, “Inflation Climbs Higher Than Expected in June as Price Index Rises 5.4%,” CNBC, July 13, 2021, https://www.cnbc.com/2021/07/13/consumer-price-index-increases-5point4percent-in-june-vs-5percent-estimate.html.

2 St. Louis Federal Reserve, “M2 Money Supply,” FRED, August 17, 2021, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/M2.

3 US Bureau of Labor Statistics, “CPI Inflation Calculator,” https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm.

4 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Institutional_betrayal

5 MBI Concepts Corporation, “IBM’s Stock Buybacks Have Not Produced Societal Wealth,” April 10, 2021,. http://www.mbiconcepts.com/ibms-stock-buybacks.html.

6 Kendall, Graham, “The First Moon Landing Was Achieved With Less Computing Power Than a Cell Phone or a Calculator,” July 11, 2019, https://psmag.com/social-justice/ground-control-to-major-tim-cook.

7 “Moore’s Law Graph,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moore%27s_law#/media/File:Moore’s_Law_Transistor_Count_1970-2020.png.

8 Bloomberg, “Fed Seen Speeding Taper of Mortgage-Backed Securities in Early 2022,” Pensions and Investments Online, https://www.pionline.com/economy/fed-seen-speeding-taper-mortgage-backed-securities-early-2022.

9 “History of U.S. Treasury Bonds,” TreasuryDirect, https://www.treasurydirect.gov/indiv/research/history/histmkt/histmkt_bonds.htm.