The case of Apothio, a hemp grower embroiled in a $1 billion lawsuit against a California county, has put Initial Litigation Offerings (ILOs) into the spotlight.

And while not a new thing in the world of blockchain, ILOs show the potential the technology can have when employed as a solution to a very persisting and very expensive problem—lawsuits.

Apothio and the problem with litigation funding

Apothio LLC, a vertically-integrated hemp business based in California, is the star of a lawsuit that has the potential to revolutionize the business of litigation in the United States.

In April 2020, the company filed a lawsuit against its native Kern County and the Kern County’s Sheriff Office, accusing them of destroying $1 billion worth of hemp crop. The company claims that it suffered the largest wholesale destruction of personal property by government entities in the history of the United States and is suing the county for $1 billion worth of damages.

However, despite its very valuable crop, the company is strapped for cash and was struggling to fund the very expensive process of litigation it was about to embark on.

Since October 2021, the company has been trying to raise funds from the public to fund the lawsuit in exchange for a piece of any eventual recovery it receives from the court. As such, litigation funding isn’t anything new, especially in the United States where lawsuits like this can cost millions of dollars. Litigation funders receive a multiple of their investment if a case settles but get nothing if the case is dismissed.

According to Business Insider, the field of litigation funding has grown significantly in the past several years, with publicly traded companies and private asset managers collectively investing over $2 billion in litigants between 2019 and 2020.

LexShares, a leading litigation fund in the U.S., has invested in 103 cases since 2014. Out of the 43 cases resolved so far, 70% had a win rate, providing investors with a median annualized return of 52%.

However, litigation fundings are limited to accredited investors only, all of which must meet the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s rigorous accreditation criteria. Aside from excluding many smaller investors from the potentially lucrative business of litigation funding, it also drastically shrinks the pool of investors plaintiffs can seek funding from.

To raise the money for its lawsuit against the California county, Apothio resorted to crowdfunding. But, instead of reaching out to a small pool of accredited investors, the company decided to take a more decentralized route—a litigation offering.

The term was coined by Apothio’s lawyers Roche Freedman, known for representing the estate of David Kleiman in the controversial case against Craig Wright. The office is a pioneer in the industry and has experience navigating the vague regulation surrounding cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology.

Roche Freedman worked with Republic, a crowdfunding website, to launch Apothio’s $5 million public offering in October 2021. Last week, its minimum fundraising target was reached when a family office contributed $150,000 to the effort. A total of 151 investors have so far contributed over $344,000 to the litigation.

Replicating the success of Apotio’s ILO with Ryval

The huge interest in Apothio and the success of its ILO quickly made headlines, pushing Roche Freedman to embark on a rather ambitious endeavor—launching a proprietary ILO platform.

Kyle Roche, a partner at Roche Freedman, said that they have been working with various technology and finance partners to move ahead with the launch of Ryval, a marketplace for initial litigation offerings.

“It’s almost as basic as a GoFundMe,” Roche told Business Insider.

The marketplace, launched on the Avalanche blockchain, would tokenize litigation offerings and allow users to trade the tokens. All of the offerings would be registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and enable investors to buy into lawsuits with as little as $100. Accredited investors would be able to trade the tokens immediately, while those without proper accreditation would be subject to a one-year lockup period, Roche said.

“Our goal is to have 5 to 10 more ILOs relatively quickly once the platform is ready,” he noted, adding that Roche Freedman wouldn’t be involved in most of those cases.

Nonetheless, the law firm is currently working with Ava Labs, the company behind Avalanche, and Republic, the crowdfunding website run by OpenDeal.

The success Apothio’s case saw also revealed some of the shortcomings of the ILO. Roche said that they have received a lot of feedback from the participants of the offering and will include new features and options into Ryval.

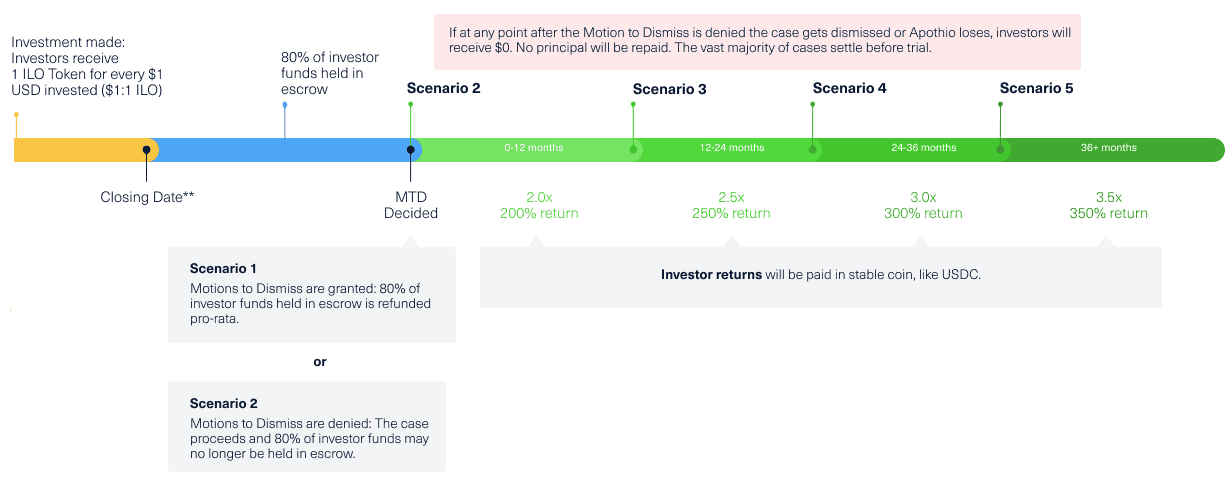

Namely, most participants said they would prefer a model that allows for more upside in the event of large recoveries. The current Apotio model grants investors 1 ILO token for every dollar invested, which will remain locked for a year. If the case is settled, the returns will depend on how much time has passed between the time the tokens were issued and the time the case was closed, ranging from 200% to 350%.

Roche said that the company was exploring how to offer a model with larger returns in future ILOs and even allow investors to get some of their money back if the case gets dismissed early.

As ILOs are a pretty new product, even in the world of crypto, Ryval will focus on providing better education about the U.S. legal system and feature some of the analytical tools used by lawyers in the country. These include statistics about case outcomes, which Roche said would help investors evaluate the risks with each lawsuit.

4) Case Data. As @TheNewsHam points out in his article, we’re working with our partners on this, and I hope to bring make the same analytical tools used by lawyers available to the public as part of the @ryvalmarket platform.

— Kyle Roche (@KyleWRoche) January 4, 2022

Kevin Sekniqi, the founder of Ava Labs, said that ILOs were a breakthrough both for individuals seeking remediation and retail investors who are often locked out of most high-performing asset classes.

“They are fundamentally unique from any other investments, and the creation of the ILO marks the first time blockchain technology will be used to democratize financial products at a multi-billion-dollar scale.”

We are yet to see whether ILOs become an asset class with real-world usability. Judging by the size of the market they’re tapping into and the perfect product-market fit they offer, ILOs have the potential to succeed. And if they do, they’ll be a perfect example of truly useful blockchain integration—one that shows that the technology isn’t a solution looking for a problem, but a very efficient way to bring the world of traditional finance into the new era.

The post Initial Litigation Offerings (ILOs) show blockchain isn’t a solution looking for a problem appeared first on CryptoSlate.