Bitcoin environmental concerns are often portrayed in misleading and exaggerated ways contrary to proper research.

Bitcoin receives disproportionate media coverage over its tiny fraction of a percent of global emissions and relatively inconsequential environmental impact. Why this happens requires following the money into environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) accounting. ESG accountants appear to be using Bitcoin’s open, transparent ledger — that can be audited by anyone in the world in real time — to exaggerate Bitcoin’s impact on the environment, with shoddy science, while profiting from the very fears they provoke.

In February 2022, an op-ed, titled “Revisiting Bitcoin’s Carbon Footprint,” was published in the scientific journal “Joule,” authored by four researchers: Alex de Vries, Ulrich Gallersdörfer, Lena Klaaßen and Christian Stoll. Their written commentary, which admits limitations in their estimates, states that as bitcoin miners migrated from China to Kazakhstan and the United States in 2021, the network’s carbon footprint increased to 0.19% of global emissions. What went unnoticed by the media was that the researchers have professional motives to overstate Bitcoin’s relatively tiny environmental impact.

The op-ed’s lead author, Alex de Vries, failed to disclose that he is employed by De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB), the Dutch central bank. Central banks are no fans of open, global payment rails, which bypass monopolistic government settlement layers. De Vries first released his “Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index” in November 2016, which coincides with his first round of employment with DNB, giving the appearance that DNB encouraged his critique of Bitcoin’s energy consumption. In November 2020, de Vries was rehired by the Dutch central bank as a data scientist in its financial economic crime unit and has been on a worldwide media tour for his “hobby” research ever since. As DNB is now promoting his research, he is effectively a paid opposition researcher for DNB.

As an employee of a central bank, de Vries has an incentive to exaggerate Bitcoin’s environmental impact to protect the interests of his employer.

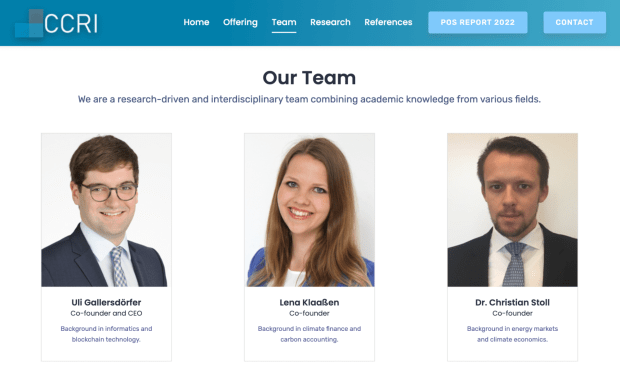

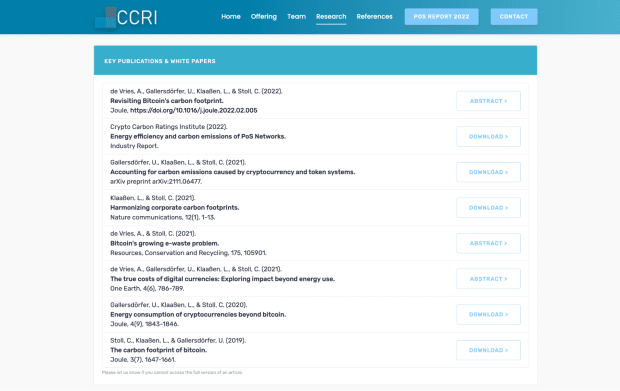

His collaborators, however, have different motives altogether. Gallersdörfer, Klaaßen and Stoll are cofounders of the Crypto Carbon Ratings Institute (CCRI), a company that provides data on the carbon exposure of cryptocurrency investments and business activities.

Collectively, the three CCRI researchers have authored almost a dozen academic papers on the environmental impact of cryptocurrencies.

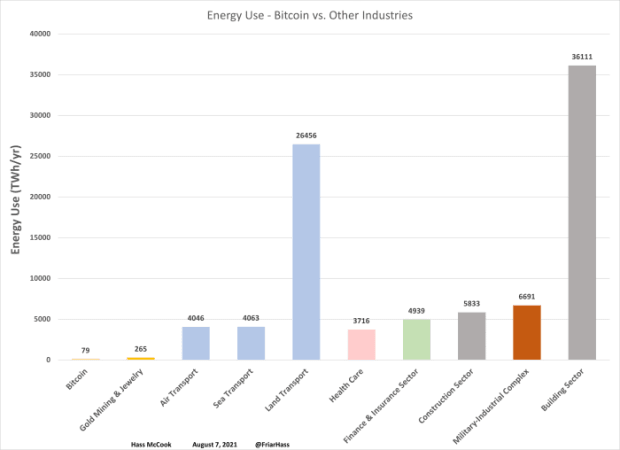

CCRI’s modus operandi is to exaggerate Bitcoin’s environmental impact through a technique the Cambridge Centre of Alternative Finance (CCAF) describes as presenter bias. This entails making apples-to-oranges comparisons — such as comparing Bitcoin to small countries — in order to elicit outrage, rather than making apples-to-apples comparisons with other industries. CCRI’s best-guess estimates on carbon emissions are then packaged and sold to financial institutions who are under pressure to disclose ESG accounting due to the investor outrage promoted by the presenter bias that CCRI itself used to provoke that outrage.

It doesn’t matter that the small countries Bitcoin is compared to have a GDP that is half of the value secured by Bitcoin. It doesn’t matter if the published papers are of a low standard or lack rigorous peer review (“Joule”’s peer review process is kept secret and does not require peer review for commentary articles). Nor does it matter that Bitcoin’s emissions are too small to have a meaningful impact on climate change. All that matters is that the media is willing to publish articles highlighting their junk science narratives, along with cherry-picked examples, and the financial industry becomes pressured to contract with the CCRI to utilize their research and data.

ESG researchers are able to profit, by leveraging the media to stoke public outrage, over what amounts to such an inconsequential amount of carbon emissions that actual environmentalists should be disturbed that the public’s attention is being distracted from larger issues that have real and substantial consequences for humanity.

Exaggerating Bitcoin’s Environmental Impact

Ironically, on Cambridge University’s Comparisons page, where it describes the tricks of ESG presenter bias, it publishes a graphic that exaggerates Bitcoin’s power consumption to look larger than it is. Here is Cambridge’s original artwork:

Notice how Bitcoin is almost the same size as industries that have significantly higher values. If the Cambridge researchers had drawn the bubbles to proper scale, it would look like this:

These kinds of comparisons don’t even tell the full story, given that Bitcoin uses more renewable energy than any of these other industries. Despite what academia and the media would have us believe, Bitcoin’s environmental impact is too small to have any meaningful impact on a global scale.

This is not to say that bitcoin miners don’t have a responsibility to be good stewards of the environment in their communities. However, those are local concerns and not particularly a good use of outsized international attention if protecting the global environment is the true goal.

When environmental researchers, the media and government devote greater than a fraction of a percent of their content discussing Bitcoin’s emissions, it becomes a disservice to environmentalism. Undue diversions only serve to virtue signal, distract from more important issues and make people less trustful of legitimate environmental causes.

CCRI isn’t solving impactful environmental issues when it admonishes Bitcoin. The company mines open blockchain data for its media-driven narratives and shames the market into buying its own data, for profit. This data allows institutional investors to claim carbon neutrality, and entice environmentally conscious investors into their products, while nothing of particular substance is achieved.

“‘ESG investing’ in its current form is similar to people who take selfies of themselves in fancy locations to show they were there, while barely experiencing it for real. Mostly theater, little substance. For example, we pollute, but buy offsets to make it someone else’s problem. We outsource our manufacturing base to another country to reduce headline energy consumption, but then buy products they make while blaming them for polluting. This is deflection, not reform…People sell their Chinese shares, buy Apple shares instead, and pat themselves on the back. Meanwhile their phone, computer, chair, sneakers, cookware, electronic devices, and kids’ toys are all partly Chinese made. A lot of it is window dressing. ‘ESG’ as currently used is corporate, sanitized, and nearly meaningless. It’s like the word ‘synergy.’ It’s a TPS report. If anything, pretending we are doing good to check off certain boxes as perceived by others, while still doing whatever we were doing before, slows real progress. One of the worst things we can do is to feel like we are doing something constructive, without actually doing so.” — Lyn Alden

Selling Proof-of-Stake Investments

The CCRI publishes an annual report to promote proof-of-stake networks as environmentally friendly while promoting a highly misleading “energy per transaction” metric. What isn’t acknowledged in the CCRI’s report is that proof of stake is not a replacement for proof of work, as the two consensus mechanisms achieve completely different goals.

Proof of work is a consensus mechanism that ensures pools of miners can collectively challenge bad actors — ensuring no one party can assert control over other users, all while providing a fair and meritocratic distribution of new coins. Proof of stake doesn’t accomplish this as it resembles a corporate security structure, where the wealthiest holders have all the voting power and founders pre-mine unimpeachable control authority over users, while receiving compounding dividends.

With proof of stake, users have to trust the founders not to denial-of-service (DoS) attack them. In proof of work, miners buy energy on an open market to make DoS attacks too expensive, which in turn allows Bitcoin to protect minority user rights. Proof of work’s energy consumption is a feature, not a bug.

Environmental researchers who claim proof of stake to be a more efficient consensus mechanism are like a policy think tank promoting plutocratic authoritarianism as a more efficient kind of government. To equate proof of stake with proof of work entirely misses the point of how decentralization works and what it intends to achieve.

But, why does the CCRI produce a report? Institutional investors commission the CCRI’s research, in order to promote centralized altcoins, while using the CCRI’s data to sell ESG-friendly “crypto” investments. By overstating Bitcoin’s global impact and promoting proof of stake as an alternative, the CCRI is effectively driving demand for institutional ESG products and its own ESG services. This isn’t about helping the environment — it’s a money-making scheme.

Bitcoin Is An Easy Target

Bitcoin’s open and transparent accounting makes it an easy target for those who benefit from exaggerating Bitcoin’s environmental impact for profit. An interesting thought experiment is to consider how environmental accountants would characterize other industries if they were as transparent about their energy consumption as Bitcoin is.

A 2020 report by the Rapid Transit Alliance estimated that the global sports industry is responsible for 0.6% of global emissions — more than three times the emissions of Bitcoin. The report uses the same presenter bias of comparing the sports industry’s emissions to that of Spain or Poland. The report states that the global sports industry generates around $500 billion a year, which is considerably less than the amount of value secured by Bitcoin.

If the sports industry had open and transparent power consumption data, like Bitcoin does, would ESG accountants shame the sports community for causing an environmental disaster? Would it be a good use of everyone’s time when there are much more important environmental issues that need to be solved?

Bitcoin As A Green Investment

It might not be evident from media reports, but Bitcoin is already a relatively green investment. A 2021 paper stated that, “adding Bitcoin to a diversified equity portfolio can both enhance the risk–return relationship of the portfolio and reduce the portfolio’s aggregate carbon emissions.” If institutions feel pressured to make their bitcoin holdings carbon neutral, it doesn’t take much effort. According to a January 2022 report by CoinShares, “Each bitcoin would require offsetting 2.2 tonnes of CO2 per year, or roughly the same as one return flight on business class between New York to Tokyo … At a bitcoin price of 42,000 USD, this would amount to an annual cost of 0.48%.”

Even bitcoin miners that are demonized in the press, like Greenidge Generation Holdings, have made their entire mining operations 100% carbon neutral without considerable effort. Greenidge uses offset project registries that fund projects to sequester and reduce emissions.

And yet, Bitcoin is a powerful, location-agnostic, buyer of last resort of renewable energy, that balances grid loads, can fund renewables stymied by lengthy interconnection queues to congested grids, and helps mitigate flared methane gas. When one realizes that Bitcoin is a solution to help monetize inefficiencies in the renewable energy sector — and as a zero-sum game increasing green mining disincentivizes carbon-intensive mining — some interesting ideas begin to take shape.

Incentive Offsets

In a paper authored by Troy Cross and Andrew M. Bailey, “incentive offsets” are proposed as a way for investors to make bitcoin holdings carbon neutral by investing just 0.5% of their holdings in green bitcoin mining operations. Unlike other proposals to green bitcoin, theirs promotes Bitcoin adoption, preserves the fungibility of bitcoin and costs nothing, while providing a return. Cross recently discussed the idea with Peter McCormack on an episode of “What Bitcoin Did” as well as during a follow-up conversation with Nic Carter.

ESG Misinformation

ESG advocates are perhaps unlikely to endorse any form of green bitcoin mining, as it would effectively neutralize their conflicted narrative. Already de Vries et al. went out of their way to peddle misleading arguments, in their op-ed, to criticize green mining and downplay its role in environmental solutions.

For example, they suggest flared gas mitigation through mining offers limited benefits but ignore the fact that wind and diminishing stack flow rates make bitcoin mining significantly more efficient and ecological than allowing methane to flare and potentially vent into the atmosphere. Environmentalists have recently acknowledged that methane is much a larger problem than was previously realized.

Or when de Vries showed Bitcoin’s energy consumption rising after China banned bitcoin mining, which resulted in a well-publicized 50% drop in hash rate. De Vries declined to include it in his estimates and dismissed it by saying, “Because of the previous challenges in determining the most likely energy consumption impact, any adjustment would be arbitrary. For this reason, no adjustments were made to reflect immediate impact of the ban.” This is effectively an admission his own estimates are spurious. De Vries has made an ESG career on top of a debunked “energy per transaction” metric, while 100% double counting the same footprint onto investors.

In a paper written by de Vries and Stoll, in 2021, the two erroneously estimated that the average service life of a Bitcoin ASIC miner was only 16 months. This is blatantly false and easily disproved by on-chain data which shows Bitmain S7s, that are seven years old, are still actively used by miners. By weaponizing academia, fraudulent assertions are repeated by the media without fact-checking. In reality, Bitcoin accounts for an estimated 0.05% of global e-waste and since ASIC miners don’t have batteries or complex systems, the parts are easily recyclable.

When misleading arguments are used to dismiss Bitcoin’s environmental efforts, while simultaneously overstating its footprint, it becomes evident that critics are not acting in good faith. How can they be when they have glaring conflicts of interest?

The ESG community has an ethics problem where its own architects profit off of the hysterics they generate and often fail to disclose those conflicts of interests to the public as their junk science narratives are amplified by the media. Exaggerated comparisons, deceptive arguments and profit-driven motives leaves the public with the perception that criticizing Bitcoin’s relatively miniscule footprint does not stem from a selfless and courageous act of environmentalism. Rather, it appears that Bitcoin critics have professional motives in mind, and a desire to maintain the status quo, that make their claims ethically questionable.

Bitcoin, of course, does not care. Renewables need Bitcoin more than Bitcoin needs renewables. The ESG industry can extract Bitcoin’s data, exaggerate its externalities and downplay any progress to profit through green institutional investment products. Bitcoin will keep on producing blocks and paving the way for open payment rails with honest, incorruptible proof of work. All the while, miners will buy up every stranded and wasted megawatt of renewable energy and give it a fighting chance to make headway in the market. The future of energy production is bright and Bitcoin will use it to incentivize innovation and human flourishing.

This is a guest post by Level39. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.