Comparing Bitcoin to barbed wire from Timothy May’s “Crypto Anarchist Manifesto” can give insight into the gravity of this seemingly abstract invention.

Some of Bitcoin’s properties sound abstract. Properties like digital ownership, censorship resistance, decentralization and more. But the deeper you dig into the Bitcoin rabbit hole, the more you realize that Satoshi Nakamoto even implemented some mutually exclusive properties simultaneously: freedom of privacy and property rights. In fact, Bitcoin reconciles an uncensorable pseudonymous system and an extreme form of property rights. I would like to show why this combination was actually almost impossible by using an analogy based on the example of barbed wire in Timothy C. May’s “Crypto Anarchist Manifesto.”

We first find the “barbed wire” analogy in one of the shortest but most exciting texts of the cypherpunk movement, the aforementioned “Crypto Anarchist Manifesto.” While the common man had never heard of the internet at the time, the minds of the cypherpunks, who were only forming in the early 1990s, had already painted a clear picture of the information age and its promises and dangers. Those who find the thesis in “The Sovereign Individual” to be prophetic should definitely keep in mind what the cryptography anarchists were already discussing a decade earlier.

With works like “Security Without Identification: Transaction Systems To Make Big Brother Obsolete” by David Chaum in 1985, this once-nascent movement set a counterpoint to the tendencies of technology moving toward centralization and control, even if this actual danger was still a long way off. May was a libertarian-minded former Intel employee who had retired from the company at 35. He became a cofounder of the cypherpunks email list and wrote influential texts. Among them was the “Crypto Anarchist Manifesto,” which he distributed at a hacker conference in 1988.

In it, May points to the great future of cryptography, which would eventually realize the grand vision of anonymity and privacy in cyberspace. In what is an almost frighteningly visionary essay from today’s perspective, May shows what possibilities encrypted communication between people could offer. He not only compared encrypted communication to the invention of the printing press, but chose an analogy that had it all: the invention of barbed wire.

May wrote, “Just as a seemingly minor invention like barbed wire made possible the fencing-off of vast ranches and farms, thus altering forever the concepts of land and property rights in the frontier West, so too will the seemingly minor discovery out of an arcane branch of mathematics come to be the wire clippers which dismantle the barbed wire around intellectual property.”

Interestingly, it is clear from the comparison that the imminent (state) surveillance and restriction of the individual goes hand in hand with the invention of barbed wire. It is cryptography, however, that cuts the barbed wire around intellectual property. From today’s perspective, the mental image May chose to paint can hardly be surpassed in terms of genius and ambivalence. After all, thanks to Bitcoin, the image even works in two directions.

Barbed wire is an often underestimated invention, and few people knew what implications it would hold. In the U.S., the so-called “frontier,” or the borderland between the settled or “civilized” and the undeveloped areas, had moved farther and farther west. It was seen as a divine mandate, a “Manifest Destiny,” to settle the whole country. To this end, President Abraham Lincoln had launched the Homestead Act in 1962. It stated that any “honest citizen” could take up land free of charge. All one had to do to claim his property was to make it his own through agricultural use.

But tilling the fields in the vast prairie was difficult, for the land was practically a single open space. It was inhospitable, overgrown with wild grasses, sometimes difficult to access and used by cowboys, ranchers or Native Americans, sometimes almost nomadically. Fencing off land was either expensive or ineffective because neither wooden fences nor planted hedges could keep out unwelcome visitors.

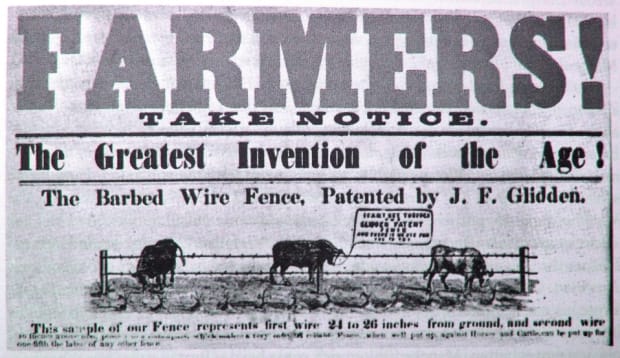

A single and, at first glance, tiny invention changed everything from the nature of agricultural use to the treatment of public lands and even the concept of ownership: the invention of barbed wire. The new type of fence was advertised in 1875 as the “Greatest Discovery of the Age.” Patented by Joseph Glidden of Illinois, it was “lighter than air, stronger than whiskey, cheaper than dust.” And indeed, it brought about a transformation of the American West. The double, twisted wire with spikes was used everywhere: by railroad companies demarcating their lines, by ranchers demarcating fields or raising cattle and by anyone else who used it to mark and protect what was “theirs.”

Barbed wire was a double-edged sword. Settlers loved it because it made property a fact. Cowboys, who used the free land extensively, hated the dangerous wire that led to injury and infection. Native Americans were driven farther and farther off their land because their concept of property was not to draw firm boundaries. No wonder they quickly referred to barbed wire as “the devil’s rope.” Old-time cowboys also lived by the principle that the great prairie was common property and cattle could run free under the law of “open range.”

Barbed wire was a disruptive invention and a fight quickly broke out over it. In the “fence-cutting years,” masked gangs like the Javelinas or Blue Devils cut fences and threatened settlers who put them up until lawmakers stepped in. The barbed wire was to remain.

It is interesting that cypherpunk Timothy C. May uses the analogy of barbed wire to counter-image the invention of cryptography. It was an equally underestimated and seemingly small invention, but one that successfully played “wire-cutter.” The ideal of the free “open range” was restored and unlike the gangs that ended up being taken down, mathematics was simply unstoppable.

The mental image is great because it turns the logic on its head. Barbed wire drew boundaries in freedom. But a tiny pair of wire cutters can undo them. And, as if with a battle cry, the “Crypto Anarchist Manifesto” ends, “Arise, you have nothing to lose but your barbed wire fences!”

Today, with Bitcoin, one of the cypherpunks’ visions has arrived in reality. In fact, we are exactly on the path that the “Crypto Anarchist Manifesto” had prophesied, in both cryptographic and economic terms. The text said that cryptographic methods would, “fundamentally alter the nature of corporations and of government interference in economic transactions.” We are well on our way to that reality, thanks to Bitcoin.

But despite how unappealing the image of the barbed wire that divided a vacant land into plots may seem to us, Satoshi Nakamoto’s mathematical-economic invention has a few similarities to the disruptive invention of barbed wire in the 19th century. At first glance, Bitcoin is also a small mathematical discovery that comes across as unassuming, but Bitcoin fundamentally changes a few things.

The ambivalence is that, on the one hand, it is indeed the vision of an “open range” that cuts through resistance, borders and (government) surveillance like wire cutters. On the other hand however, Bitcoin allows precisely the effortless demarcation of ownership. Bitcoin is a bit like “barbed wire” for property rights in the digital world. This is because it is the ingenuity of this invention, cryptographic encryption in conjunction with the timechain, that turns what was initially only a theoretical right to property into a reality.

This is because Bitcoin transactions, although pseudonymous, show many formal aspects of property rights as we know them from real estate. For example, ownership is publicly registered and shown without gaps across the interconnected blocks. This ownership is publicly accessible and verifiable for each individual. And it is ensured that no duplicate claims exist. The timechain becomes a kind of public land registry. Transferring these features and processes to a pseudonymous system is indeed unique — barbed wire and wire cutter at the same time.

While critics of the technology bother with superficial analogies like the tulip mania, Bitcoiners know that fundamental philosophical debates underlie all the issues at stake in Bitcoin. Philosophers like John Locke or Jean-Jacques Rousseau would write entire books about the fundamental questions of this digital commodity, if they were still alive.

After all, what do we actually own besides our bodies? That which we cultivate with our work? That which we transform? Or simply that which we can demarcate?

This is a guest post by Holger von Krosigk. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc. or Bitcoin Magazine.