Adopting bitcoin on Veterans Day can help put an end to forever wars that unnecessarily risk the lives of U.S. soldiers.

This is an opinion editorial by Captain Sidd, a finance writer and explorer of Bitcoin culture.

On the occasion of Veterans Day in the U.S., I wanted to put down a few thoughts on war. War is a vile thing, yet likely millions of people around the world actively engage in it every year with over a quarter of the world’s population currently living in “conflict-affected areas” according to the UN.

America, for its part, is almost constantly engaged in armed conflicts around the world, either in an advisory capacity, with air and missile strikes, or with U.S. troops joining the fight directly. President Obama, who ran on a platform of ending U.S. intervention in Afghanistan and Iraq, was the “first president to serve eight years and preside over American wars during every single day of his tenure,” per NPR. While he did reduce the number of American troops exposed directly to combat zones (from 180,000 to 15,000), he greatly expanded drone capabilities and supposedly-targeted killings, leading to a tenure where, in 2016, every day was marked by three bombs dropped on unsuspecting heads.

Even today, under an administration that slowed drone strikes on suspected terrorists, we now seem to be on the precipice of World War III. One of the world’s largest energy producers — Russia — invaded its neighbor — Ukraine — a breadbasket nation with aspirations to join the NATO military alliance.

Beyond conventional wars, societies today find themselves muddled in endless ideological and abstract wars that also harm people and claim lives — some in numbers far exceeding conventional wars. Several American examples include the War On Poverty, the War On Drugs and the War On Terror.

How did we get to a world of endless wars, and what can we do about it?

To answer that, we need to start with what keeps war going: funding.

War Is Expensive

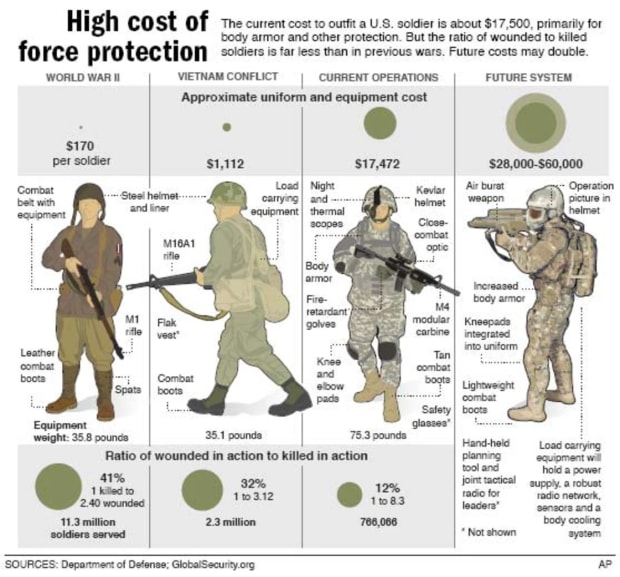

Putting troops into combat zones, arming them and feeding them is no cheap venture. The U.S. military spent a record $801 billion to keep the machine running in 2021 alone. While military spending is dropping as a percentage of GDP in the U.S., it is still around 4% for the past 20 years.

Ideological wars also rack up immense costs, though these are harder to quantify in some cases. The costs of the War On Poverty launched by President Johnson in 1964 are estimated to total over $22 trillion as of a 2014 study by The Heritage Foundation. Don’t like Heritage’s politics? Consider The Washington Post’s fact check of Paul Ryan’s claim that $15 trillion was spent on the War On Poverty up to 2013. While the article claims Ryan is misleading with the figure, it offers no other concrete figure and can only muster around $1 trillion of possible overestimation.

The costs of the War On Drugs are lower in monetary terms — around $1 trillion — but the second-order effects of unregulated drugs and warring violent gangs create an undoubtedly large burden on healthcare and policing systems. This is not to mention the cost in human lives, with Mexico counting over 300,000 deaths in its country due to the War On Drugs between 2014 and 2020. That’s equal to the amount of Americans lost in the second world war.

The War On Terror gathers shocking numbers as well, with over $8 trillion spent by the U.S. on the post-9/11 military interventions. The misadventures of violent “nation building” in far-flung lands also create economic costs, keeping countries and communities on their knees and unable to grow or prosper.

However, all of these pale in comparison to spending on the 20th century’s total wars. The total wars of the 1930s and ’40s resulted in a massive amount of spending, with World War I costing the United States about 52% of gross national product and World War II running up a bill equaling 40% of GDP.

Where does this money come from?

Funding Sources For War

Governments are only able to engage in lengthy and costly wars through funding — so where does the money come from?

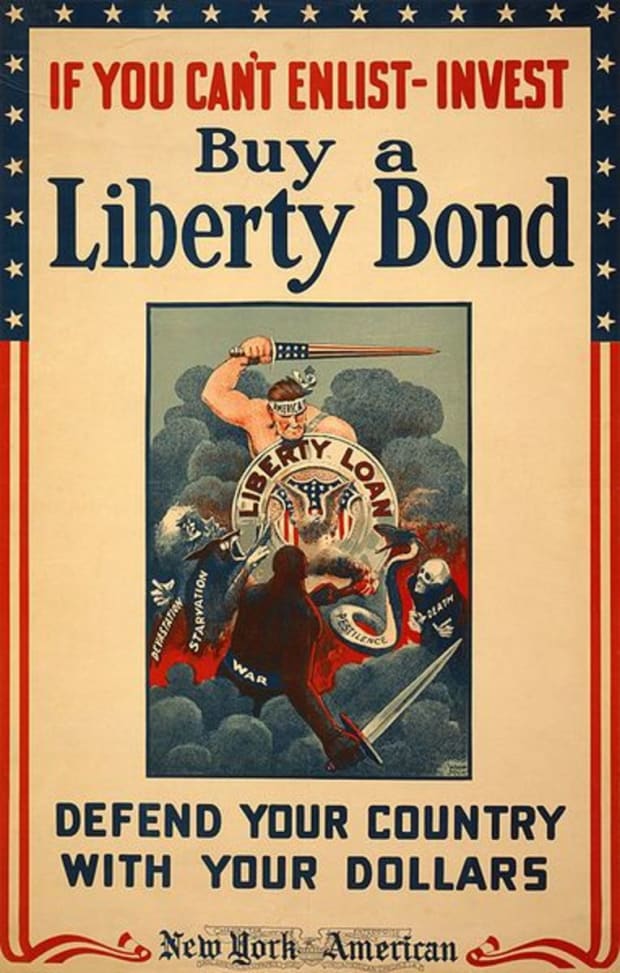

The first funding method is borrowing. Governments can issue “war bonds” that give the buyer a monetary return after the war concludes. In return, the government gets much-needed cash now. In the past, the public was encouraged to buy these bonds as their patriotic duty. Hugh Rockoff of the National Bureau of Economic Research estimates the U.S. raised 58% of the funds used to wage World War I through borrowing from the public.

The second funding method is taxation. Governments can levy taxes to fund war efforts, drawing down from the public’s coffers directly. Rockoff estimates the U.S. effort in WWI received 22% of its funding from taxation. Taxes were raised through the War Revenue Act of 1916, which taxed “profits exceeding an amount determined by the rate of return on capital in a base period — by some 20 to 60 percent,” per the National Bureau Of Economic Research (NBER). Income taxes also rose at top income brackets from 1.5% to over 18%.

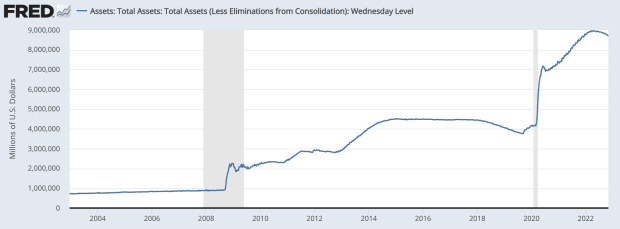

The final funding method is money printing. The mechanics of this method vary by country, but usually involves a central bank buying the bonds (debt) of their own country’s treasury using freshly-printed (or keystroked-into-existence) cash. While this only accounted for 20% of WWI funding in the U.S., per NBER, borrowing from our central bank is now an increasingly-popular option for politicians wanting to put cash toward all sorts of pet projects.

While borrowing requires counterparties willing to lend, and taxation raises the public ire, printing money is a much more palatable option politically. It allows for spending now without needing to make hard choices or immediate sacrifices. As the U.S. military and foreign influence grew over the 20th century, America’s ability to borrow from its own central bank increased.

The party almost came to an end due to heavy spending on the Vietnam War and the War On Poverty in the 1960s, which led nations like France to trade in their dollars for gold. At the time, the U.S. dollar was backed by gold at a rate of $35 to one ounce of gold. Foreign governments could thus trade their dollars in for gold at any time, and the U.S. government had to honor that rate — however, there were so many quietly-printed dollars in circulation by the late 1960s that the rate should have been around $200 to one ounce of gold.

Nixon decided in 1971 to “temporarily” take the U.S. dollar off the gold standard — though it never returned. Without any hard, unforgeable money backing the U.S. dollar, the government was free to proudly print money, taking purchasing power from all wage-earners and holders of U.S. dollars to support government programs.

With money printing, waging war virtually forever is now possible. Whereas taxation and borrowing dry up when citizens openly defy the war, printing money requires far less oversight or agreement from the people.

Let’s look at a few recent “forever wars” that survived through printed money.

The War On Poverty

The War On Poverty originated in the mid-1960s with legislation creating and expanding federal aid programs aimed at poverty alleviation. These programs include the Job Corps, which helps place disadvantaged youths into jobs, and the Volunteers In Service To America (VISTA), a domestic version of the Peace Corps aimed at helping the poor in America.

The goal of the War On Poverty, as stated in Lyndon B. Johnson’s 1964 State Of The Union Address, was “not only to relieve the symptom of poverty, but to cure it and, above all, to prevent it.” Was the War On Poverty effective toward those ends?

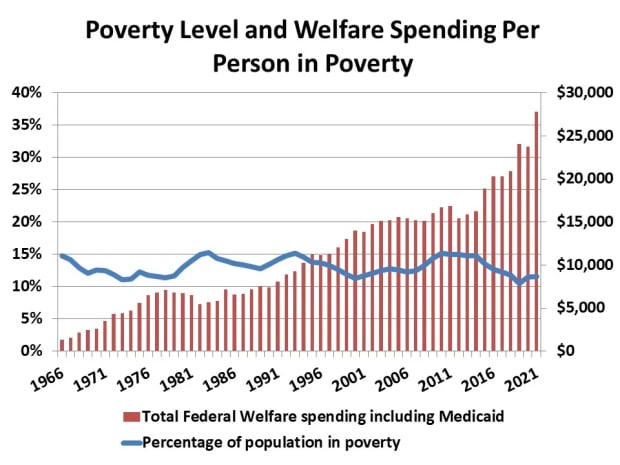

While some of the many federal programs created to address poverty helped individuals in certain times and places, the overall results are not positive. While the U.S. government spent vast and increasing sums on poverty alleviation, the rate of poverty has hovered between 10% and 15% for decades.

Poverty actually declined steadily into the 1964 launch of the War On Poverty, from over 22% in 1959 to around 17% when the Economic Opportunity Act was signed into law in August 1964. This poor performance of the War On Poverty also sits against a backdrop of rising income inequality, where the middle class dropped from 62% of U.S. aggregate income down to 43%, with the upper income bracket taking up that entire drop.

How could this war go on for so long, consuming more and more resources without producing results? The U.S. government printed more money, borrowing from the future and from its own central bank — which began expanding its balance sheet in the 1960s for the first time since WWII concluded. Without the ability to print U.S. dollars, the government’s ability to wage misadventurous wars in poverty and in Vietnam simultaneously would have been severely limited.

The War On Drugs

The War On Drugs began in the 1970s with Richard Nixon declaring drug abuse public enemy number one. In the past 50 years, despite military interventions and strict policing around the world, drug use and abuse is still rampant and causing accelerating deaths.

Drug overdose deaths steadily rose over the past 20 years according to the NIH, and a 2018 poll found that less than 10% of Americans think the War On Drugs is being won. Meanwhile, incarceration for drug offenses is destroying education and employment opportunities, creating an underclass of many disadvantaged and often Black or Hispanic people. Why does the War On Drugs continue, then?

Unfortunately, the War On Drugs does not need popular support. The money printer allows funding for the system of policing and prisons needed to continue the war. Without the pain of taxation or the choice to lend to the war effort, the public’s ire never reaches the fever pitch needed to change political tides. The War On Drugs is now unaccountable, a rogue government program with few checks on its spending or actions. What we are left with is an institutionalized destruction of society, kept alive by the money printer.

The War On Terror

The War On Terror began following the September 11 attacks, and put American troops throughout the Middle East to stomp out al-Qaeda and other extremist groups.

While the War On Terror claimed a victory in the death of Osama bin Laden, the evolution of America’s 20-year war claimed an estimated one million lives, with a third of those being civilians. Meanwhile, new terror groups sprung up and evolved during U.S. occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan, leading to the rise of ISIS. At home, the War On Terror served as a convenient excuse to pass sweeping surveillance measures through the Patriot Act.

Perhaps the most poignant example of the War On Terror’s failure was the U.S. exit from Afghanistan. After 20 years of U.S. military occupation, U.S. intelligence estimated the Taliban would take back Kabul in 30 to 90 days after U.S. troops withdrew. It took them just five days.

A million lives lost, $8 trillion spent, and what do we have to show for it? Very little, considering the Middle East is likely less stable and more likely to harbor terrorists today than when the War On Terror began. The war was able to continue, despite a lack of direction or success, due to its unaccountability. There were no clear metrics to measure success and no voters complaining about increased taxation to cover the war’s costs. This is enabled in large part by the massive deficits the U.S. government now runs to wage forever wars.

Why Do We Wage These Wars?

All of these examples of American forever wars were abject failures at achieving their stated aims, yet our government still spends time, energy and money waging them. Why are these clearly-failed wars still funded?

They receive funding because printing money leads to unaccountable programs. Citizens do not sign off on printing money to fund these programs, and they feel no increased taxes or cuts in other areas that affect them. It’s unclear exactly what — if anything — citizens are giving up to fund government programs today. Even when the public voices opposition to a war, that opposition has no teeth.

Voting out politicians who support an unpopular forever war leads to a game of whac-a-mole. There are always more aspiring politicians vying for control over the money printer to fund their own pet projects or forever wars, so the core problem remains unsolved.

Additionally, powerful corporations in the military industrial complex and other recipients of government money have a vested interest in keeping the payments flowing. Those structures have every incentive to keep politicians in power who support using the money printer to pay them, at the expense of the wage earner and middle class.

How does Bitcoin change any of this?

Bitcoin Limits War

Widespread adoption of bitcoin as a monetary unit, in place of fiat currencies like the U.S. dollar, would tightly control or completely eliminate a government’s ability to print money. Just as the gold standard kept U.S. spending largely in check, a bitcoin standard will limit spending on military adventures abroad and costly programs at home. Government programs will need the support of the people to continue receiving funding, or else the increased taxation needed to fund those programs will lead to voting out politicians who support them. The feedback loop of rising spending between government and supported industries — like the arms industry in the U.S. — will largely disappear as public sentiment plays a larger role in allocation of government funds.

I am hopeful we can achieve a bitcoin standard because doing so does not require us to lobby the very politicians who benefit most from the existing monetary system. Achieving a bitcoin standard only requires that we as individuals and communities continue to adopt bitcoin to a greater degree as a savings tool and monetary medium. If we all hold and transact in bitcoin instead of fiat currencies, the fiat money printer has nobody to suck purchasing power from and the politics of money printing will necessarily reform.

Let’s honor our military veterans by only putting soldiers into war when absolutely necessary. Our collective and peaceful actions can end the funding source for unaccountable, brutal and life-destroying forever wars.

This is a guest post by Captain Sidd. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.