We review market making basics, liquidity provisioning on centralized and decentralized exchanges, and ponder what the future of market making may hold.

Market Making Basics

Market making is the act of providing two-sided quotes – bids and asks – along with the quote sizes for an asset on an exchange. Doing so increases liquidity for buyers and sellers, where they otherwise may have seen worse pricing and less market depth. In theory, market makers earn the bid-ask spread – for example, buying an asset for $100 and selling it for $101 – in return for taking on price risk.

In practice, however, crypto assets are volatile and there is often limited two-sided flow, making the bid-ask spread difficult to capture. As such, market makers typically seek to meet KPIs around bid-ask spread, percentage of the time the market maker is the best bid and best offer (known as top of book), and uptime to earn fees while keeping risk low.

Market makers use proprietary software, often referred to as an engine or bot, to show two-sided quotes to the market, with the engines constantly adjusting bids and asks up and down based on market price movements.

The quality of market making services varies significantly by market maker, with key differentiators including liquidity provided and adherence to KPIs, technology and software, history and experience, transparency and reporting, reputation and support of fair markets, exchange integrations, liquidity provisioning across both centralized and decentralized venues, and value-added services such as OTC trading, treasury services, strategic investment, and industry network, knowledge, and advisory.

The benefits of market making are vast – greater liquidity and market depth, reduced price volatility, and dramatically reduced slippage to name a few. But perhaps most importantly, market making provides a pivotal function for the crypto ecosystem, as tokens are what makes the technology work.

CEXs vs. DEXs

Market making by professional firms has traditionally taken place on centralized exchanges, though it’s increasingly occurring on decentralized exchanges as well. The differences are:

Centralized Exchanges

Centralized exchanges are intermediary platforms connecting buyers and sellers, and examples include Binance and Coinbase. Assets on a centralized exchange have a bid price, defined as the maximum amount anyone on the exchange is willing to pay for an asset, and an ask price, defined as the minimum amount anyone on the exchange is willing to sell the asset for.

The difference between the bid and the ask price is the spread. Note that there are two main types of orders, maker orders and taker orders. Maker orders are where the buyer or seller places the order with a defined price limit at which they’re willing to buy or sell.

Taker orders, by contrast, are orders that are executed immediately at the best bid or offer. Importantly, maker orders add liquidity to the exchange, while taker orders remove liquidity, and as such, many exchanges charge a lower fee or even no fee at all for maker orders.

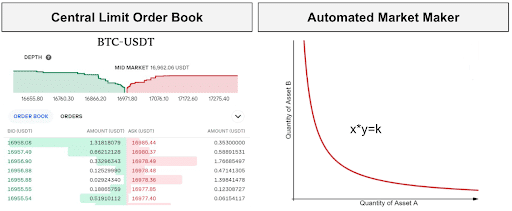

Bids and asks are then encompassed in an exchange’s central limit order book (CLOB), which matches customer orders on a price-time priority. Taker orders are executed at the highest bid order and the lowest ask order.

Market participants can also see order book depth, i.e. bids and asks beyond the highest bid order and lowest ask order, called top of book. Market makers connect their trading engines to automatically provide bids and asks on a certain cross and are constantly sending bid and ask orders to exchanges.

Decentralized Exchanges

Some market makers provide liquidity on decentralized venues as well. Central limit order books used at centralized exchanges may be difficult to use on a decentralized exchange, as the cost and speed limitations of many layer ones make the millions of orders placed per day by market makers impractical.

As such, many decentralized exchanges use a deterministic pricing algorithm called an automated market maker (AMM), which utilizes pools of tokens locked in smart contracts called liquidity pools. AMMs work by allowing liquidity providers to deposit tokens, often in equal amounts, into a liquidity pool.

The price of the tokens in the liquidity pool then follows a formula, such as the constant product market maker algorithm x*y = k, where x and y are the amounts of the two tokens in the pool and k is a constant.

This results in the ratio of tokens in the pool dictating the price, ensures that a pool can always provide liquidity regardless of the trade size, and that the amount of slippage is determined by the size of the trade compared to the size and balance of the pool.

As the price in the liquidity pool deviates from the global market price, arbitrageurs will come in and push the price back to the global market price. Various protocols iterate on this basic AMM model or introduce new models to offer improved performance for things like highly correlated tokens (Curve), many-asset liquidity pools (Balancer), and concentrated liquidity (Uniswap V3), as well as extend to derivatives such as with virtual AMMs for DeFi perpetuals protocols.

Note that with the progress of newer layer one blockchains and layer two scaling solutions, several DEXs follow a more traditional central limit order book model, or offer both an AMM and a CLOB.

Liquidity providers in a liquidity pool receive trading fees in proportion to the liquidity they provided to that pool, and they may also receive protocol tokens that the protocol uses to incentivize liquidity in what’s called liquidity mining.

Liquidity providers are exposed to impermanent loss, which is where one of the two assets provided to the pool moves materially differently than the other, causing the liquidity provider to have been better off by simply holding the two assets outright rather than providing the liquidity.

State of the Market

The cryptocurrency market has many unique characteristics, leading to various challenges when providing liquidity. For example, crypto markets are open 24/7/365, offer the ability to self-custody, has retail interact directly with the exchange, offer instant “settlement” of virtual balances at CEXs and fast settlement of on-chain trades at DEXs compared to T+2 traditional finance settlement, and use stablecoins to facilitate trading, given BTC volatility and still-clunky fiat to crypto conversion.

In addition, the crypto markets are still largely unregulated, leading to the potential for price manipulation, and continue to be highly fragmented, with liquidity bifurcated across many on and off-chain venues. In addition, trading venue technology is still evolving, as exchanges have varying quality of API connectivity and may go down during times of particularly high market activity.

Lastly, the crypto derivatives market is still evolving, with derivatives commanding a smaller percentage of total market volume compared to traditional financial markets.

These characteristics have led to various challenges when it comes to providing liquidity, including market fragmentation / interoperability, poor capital efficiency, exchange risk, regulatory uncertainty, and still-improving exchange technology / connectivity.

The Future of Market Making

The crypto industry continues to evolve at a breakneck pace, and crypto market making is no exception. We see the following current and potential future trends:

Institutionalization

The crypto market is becoming more institutional by the day, and the importance of liquidity providers will only increase as institutional demand grows.

Interoperability

Interoperability should improve, particularly in DeFi as cross-chain bridging solutions improve and composability comes to the fore. We see a multi-chain world eventually fully abstracted away from the user, including market makers.

Capital Efficiency

Liquidity providers on centralized venues have to fully fund their order books at each exchange, given fragmented markets and an inability to cross-margin. In the future, greater credit extension through the use of crypto prime brokerages and a more formalized repo market could improve capital efficiency.

Within decentralized exchanges, continued progress on concentrated liquidity provisioning, undercollateralized credit extension, liquid staking, cross-protocol margining, and advances in settlement speed should aid capital efficiency.

Exchange Risk

Given recent events, market makers are likely to reduce capital on centralized venues and cease trading altogether on less trusted, less regulated exchanges to minimize exchange counterparty risk.

Market makers and other participants may look to reduce the functions of centralized exchanges, which currently play the role of broker, exchange, and custodian, perhaps through solutions that allow trading on top venues directly from third-party custodians, such as with Copper’s ClearLoop.

Exchanges, for their part, will likely try to entice liquidity through lower trading fees and increased transparency, the latter of which is starting to occur with several exchanges releasing proof-of-reserves.

DeFi vs. CeFi

DeFi is likely to grow faster than CeFi, given its native trustlessness and ability to self-custody, faster innovation from being earlier in its life cycle, progress on current challenges such as improved gas fees, MEV-resistance, and greater insurance options.

Regulation, however, is likely to be a key determinant, with its ability to slow DeFi adoption should regulators take a heavy-handed approach to DeFi, or spur growth, should clear but sensible guardrails be instituted to foster innovation.

DeFi Derivatives

Given the prevalence of derivatives in traditional financial markets, DeFi derivatives volumes, and thus DeFi derivatives market making, are likely to grow faster than spot DeFi volumes. This may be particularly true for options, where growth has so far lagged relative to perpetuals.

Protocol Driven Liquidity

DeFi protocols often incentivize liquidity provisioning through liquidity mining, where the protocol gives its native token to users in exchange for providing liquidity on a DEX. Such liquidity, however, is often fleeting, leaving once the liquidity mining incentives run out.

A host of projects such as Curve, Tokemak, OlympusDAO, and Fei/Ondo offer innovative on-chain liquidity direction, often through protocol-controlled value, where the projects themselves acquire funds to support their protocols rather than utilize users’ funds by incentivizing them with liquidity mining rewards.

About GSR

GSR has nine years of deep crypto market expertise as a market maker, ecosystem partner, asset manager, and active, multi-stage investor. GSR sources and provides spot and non-linear liquidity in digital assets for token issuers, institutional investors, miners, and leading cryptocurrency exchanges.

GSR employs over 300 people around the globe, and its trading technology is connected to 60 trading venues, including the world’s leading DEXs. We have a culture of approaching complex problems with tenacity and imagination.

We build long-term relationships by offering exceptional service, expertise and trading capabilities tailored to the specific needs of our clients.

Find out more at www.gsr.io.

Follow GSR for more content: Twitter | Telegram | LinkedIn

Required Disclosures

This material is provided by GSR (the “Firm”) solely for informational purposes, is intended only for sophisticated, institutional investors and does not constitute an offer or commitment, a solicitation of an offer or commitment, or any advice or recommendation, to enter into or conclude any transaction (whether on the terms shown or otherwise), or to provide investment services in any state or country where such an offer or solicitation or provision would be illegal. The Firm is not and does not act as an advisor or fiduciary in providing this material.

This material is not a research report, and not subject to any of the independence and disclosure standards applicable to research reports prepared pursuant to FINRA or CFTC research rules. This material is not independent of the Firm’s proprietary interests, which may conflict with the interests of any counterparty of the Firm. The Firm trades instruments discussed in this material for its own account, may trade contrary to the views expressed in this material, and may have positions in other related instruments.

Information contained herein is based on sources considered to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. Any opinions or estimates expressed herein reflect a judgment made by the author(s) as of the date of publication, and are subject to change without notice. Trading and investing in digital assets involves significant risks including price volatility and illiquidity and may not be suitable for all investors. The Firm is not liable whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from the use of this material. Copyright of this material belongs to GSR. Neither this material nor any copy thereof may be taken, reproduced or redistributed, directly or indirectly, without prior written permission of GSR.

By: Brian Rudick, Senior Strategist; Matt Kunke, Junior Strategist